Who is that guy?

Of all of the literary

archetypes, surely it is

The Stranger that is most distant from true human experience. When we learn in

Shane that the

quiet ranch-hand is actually the

fastest gun in the territory (at least), or in

Kung Fu that "that Chinaman" is actually a

fearsome human weapon, a great part of the appeal is the exoticness of this discovery. In an ordinary setting, we encounter a one-in-a-million person, one who embodies complete mastery in an unexpected form.

Sometime it's pretty clear what's going to happen, as when Luke warns Jabba to "free us or die" before going through his bodyguards like

Odysseus through the suitors; or when Clark Kent

heads for the phone booth. But sometimes the audience is in dark, too - when

The Big Boss first came out, no one knew who Bruce Lee was, until right about the 45:30 mark. Then, they knew.

In

Once Upon a Time in the West, a simple murder assignment turns into a startling demonstration of Harmonica's nearly

supernatural powers.

"Did you bring a horse for me?"

It never happens in real life, of course. Such virtuosity cannot be kept hidden. Imagine someone with the skills of a Michael Jordan or a Tiger Woods trying to keep it quiet. Anyone who sees such a performer will tell everyone they know. (One of the running jokes of the Gospel of Mark is Jesus' admonitions to his followers to not tell anyone about his healing powers - admonitions which they of course ignore. When he rises from the dead he tells Mary Magdalene to rejoice and tell everyone - and of course she goes home and doesn't tell a soul, making the Gospel of Mark arguably the world's most-read shaggy dog story.)

The implausibility is trebled when we are dealing with untested youth.

Avatar: The Last Airbender is great fun in the early episodes when even Aang is not yet aware of the extent of his abilities, and the moment when he enters the Avatar State and breaks the Fire Nation's

Siege of the North (2:19) transforms a pleasant children's cartoon into something much richer and more wonderful. The delight of discovery is heightened by the implausibility of a child, from nowhere,

channeling an immense power and making a mockery of men who had thought themselves powerful.

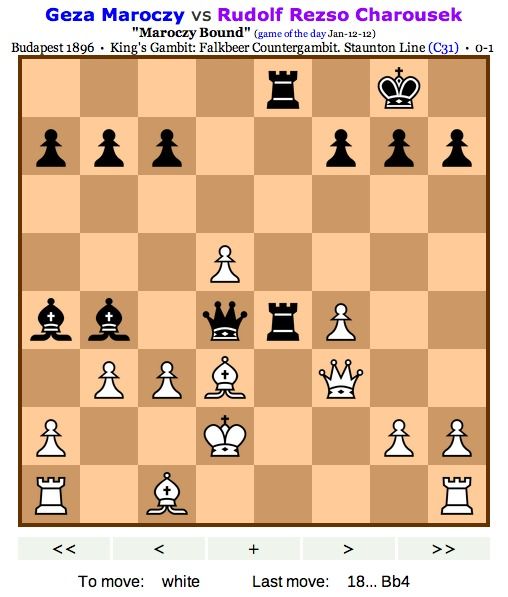

Warning: chess ahead

So Capablanca came to

San Sebastien in 1911, aged 22. Of the 15 eminent masters who had been invited - the cream of the crop (excepting only Emanuel Lasker, the Champion) - Capablanca was the only one to have never won a major tournament. They knew who he was in New York, though. He had been invited at the insistence of the American champion, Marshall, whom the Cuban had crushed in a match two years earlier.

But the Europeans had never seen him, and, from their perspective, had little to fear. The San Sebastien tournament may have been the strongest in history up to that time. Even the 'weaker' players were masters of astonishing skill, most with a decade or more of experience in world-class competiton. Virtually without exception they were the best or second-best players in their respective countries:

- Bernstein, born in Zhytomyr, Ukraine, took his degree in law at Heidelberg. He was a rising star in the chess world, having shared equal first with the estimable Rubinstein at Ostend in 1907.

- Burn, who had been taught by the immortal Steinitz himself (and subject of a great chess biography),

- Duras, the Czech who could beat everyone but Rubinstein,

- Janowski, who played even with the old guard but had trouble with the strong younger players,

- Leonhardt, a brilliant attacker, now at the peak of his powers,

- Maróczy, a Hungarian, had at one time been arguably the best player in the world, but was now merely in the top five,

- Marshall, the American attacker and swindler, strong but not versatile enough to be world champion,

- Nimzowitsch, the eccentric man from Riga who was developing his own "system" of chess,

- Rubinstein, the positional genius from Poland who chose to become a grandmaster instead of a rabbi, at this moment possibly the strongest player in the world, fully the equal of Lasker,

- Schlecter, the "drawing master", who nonetheless won 300 tournament games against only 115 losses, enough to be considered a championship contender for most of his career,

- Spielmann, an attacking specialist like Leonhardt, very dangerous on his best days,

- Tarrasch, a German doctor, correct in all things, from openings to endgames to tailored suits and moustache wax,

- Teichman, who always seemed to come in fourth, earning the nickname "Richard the Fourth",

- and Vidmar...young and energetic, he would become the founder of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering at the University of Ljubljana and play master level chess well into the 1950s.

A

portrait of the field, Capablanca seated center, looking at the camera. See how calm he looks?

He is about to crush them.

Bernstein had objected to the inclusion of the young Cuban, and he was the first to fall (

Capablanca v. Bernstein). Capablanca sat with unnatural calm, moved quickly, never committed the slightest oversight. The others fared no better. The final standings:

Source: Wikipedia - damn they're awesome

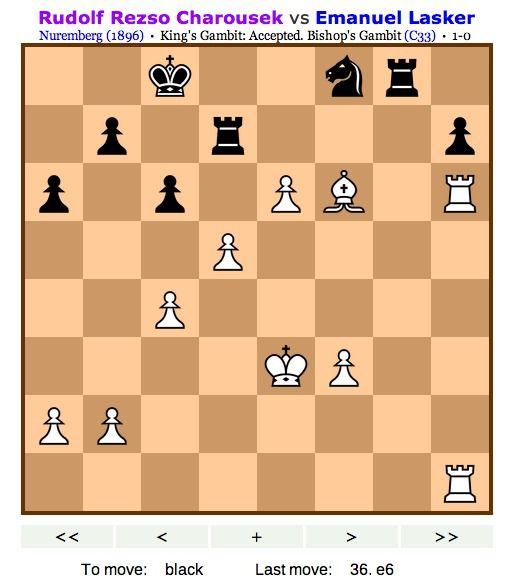

Yes, he lost a game - one - to the

immensely powerful Rubinstein. The score is

here, and it bears an odd resemblance to another great

Rubinstein victory, against Lasker, with both wins hinging on the problem-like move Q-c1.

That loss notwithstanding, Capablanca won the tournament. He got 5,000 Francs for the first prize, along with an extra 500 from Baron Rothschild for the brilliancy against Bernstein.

As the masters gathered for the closing ceremony, it must have occurred to them that the beatdown they had received was Capablanca's first experience of top-class chess. And, with the possible exception of Rubinstein, they must have realized already that none of them could ever surpass him.

Or his hair

He rapidly became invincible: from 1916-1924 his record in tournament games was 40 wins, 24 draws, and

zero losses. No one else has ever done anything remotely similar. He was so good people feared he had solved the game, though this fear ultimately proved unfounded. English grandmaster Neil McDonald comments:

This prophecy was, thankfully, never fulfilled for two reasons. Firstly, there is an inherent dynamism in positions reached from even the most symmetrical or classical openings...this means that not everything can be worked out by logic and common sense alone. It is necessary to calculate variations and make decisions based on intuition, which allows space for human creativity, poor judgment and good old-fashioned luck – and therefore wins and losses. How did Capa go eight years without losing? Well, he was a genius.

In 1920 Lasker sent Capablanca a letter resigning the championship. After much negotiation, Lasker was persuaded to play a title

match in 1921, but could not win a single game. Capablanca would hold the crown until 1929, when he lost it by a narrow margin to the master of neurosis-as-a-weapon, Alekhine. In a 1959 reminiscence, the British master C.H.O’D. Alexander, who played both men,

draws the portraits:

Capablanca knew he was much better than anyone else and took it for granted; Alekhine never quite believed it and was always out to demonstrate it yet again to reassure himself. An intensely nervous, dynamic character, the way he moved his pieces was almost like a physical attack. Capablanca gave you the impression that disposing of you was a piece of routine, to be got over as quickly as possible; Alekhine, you felt, intended to give you a lesson you would not quickly forget for your impertinence in daring to oppose him.

Many, including Fischer, believed Capablanca was the greater player. If

we believe Chessmetrics, it is so: Capablanca is in the top 5 of every list from 1 to 15 years.

Those who played against him, or watched him play, remarked on his clarity, how lucid his play was. His games unfolded as continuous, logical narratives, culminating in seemingly inevitable victory. We must remember, in 1911 chess was still largely

terra incognita - no one was sure exactly how to play correctly. But today we do know, and we can evaluate every game ever played using

chess engines that are stronger than any human player. With enough CPU cycles, we can work out the best move for almost any position.

Studies using these engines tell us which master made the fewest errors in his tournament games: Capablanca.

As Alexander notes, he did it all without apparent effort. Late in his life, his second wife Olga got her courage up and asked him about it:

He was in one of his best moods and even drank a little champagne with me. Only then did I venture the question. “The players would like to know why you don’t pay more attention to chess.”

Instead of cutting me short, as I half expected, Capa smiled. “You, too, would like to know?”

As I nodded, he said slowly and clearly: “Because if I did, there would be nothing left for the others.”

/chess

The cost of grace

Malcolm Gladwell would

have us believe that aptitude is overrated, that if you or I would just put in 10,000 hours of solid effort we too could be world-class violinists or pole vaulters. I am sympathetic - I have seen far more people become "gifted" through

hard work than through grace.

But there is grace. There are chosen ones. The Greeks knew it, and populated their stories with

demigods. The Romans had one of their own,

Aeneas, who was mothered by Venus and also had Zeus in his paternal line. Gilgamesh did them one better, achieving the genetically impossible ratio of two parts god to one part man.

I'll settle your hash when I'm done with the lion

They usually display their gifts early. Capablanca learned chess from watching his father, then announced one day that he could beat him, and did, followed in short order by the champion of Cuba. Tiger Woods watched his father practice his swing from a high chair, and took his first golf swing when he was nine months old. By the time he was two, he was on

national television. Here's

a piece by Paul Klee, which is a little weak by his standards until you learn that he did it when he was five.

Picasso and

Toulouse-Lautrec had similar moments (

NYT piece on this

here).

Ok, one more. Wayne Gretzky is a year older than I am. In 1979, I walked around hockey rinks and wrote some sports reports for a local paper, more or less waiting to grow up a little before going to college. That year Gretzky played for the WHA all-stars in a three game series against Moscow Dynamo, on a line with Gordie and Mark Howe.

They won.

Looking at these prodigies, though, I see two perhaps related problems. First of all, hardly any of them accomplished anything noteworthy beyond their core area of genius. Second, their experiences are so unique, I imagine that their lives must be somewhat lonely. Who is there who has shared their experiences? Gretzky was playing against ten year-olds when he was six. He may fit in with a group of immortal hockey players, but even with them, is there anyone who has experience what he has? Maybe Mozart had the same problem.

What else do they miss? Surely they miss the great gift of mediocrity: the ability to choose a path. There was never much doubt what Wayne Gretzky or Tiger Woods would do for a living. But those of us born with ordinary talents have to

make ourselves, and

make our lives - a gift that few appreciate.

Edward Lasker - no relation to Emanuel, though he

drew him once - is one of only a few people I can think of who chose to turn his back on great sporting or artistic potential so he could do something useful instead (he invented the breast pump, among other things). Vidmar (mentioned above) was another. But you don't see many.

To make things worse, The Gift usually imparts a cost of narrowness, even among those who wish for broader horizons. Emanuel Lasker pursued various creative projects, but they are forgotten now. Einstein lamented that chess had twisted the mind of his friend in some way- "the enormous mental resilience, without which no chess player can exist, was so much taken up by chess that he could never free his mind of this game, even when he was occupied by philosophical and humanitarian questions."

I am still working my way through Gladwell's book, but there is something else these people have, something that I believe is decisive in their separation from the rest of us. It is, for want of a better word,

sight. Larry Bird and Wayne Gretzky were not astonishingly strong or fast - what was astonishing about them was their perception, their awareness, their anticipation. Watch Tiger's eyes around 1:08 of

this clip and tell me he's not seeing something no one else sees. These people see things, and once they see them, they are changed and cannot return to a normal life, if they ever had one.

Lasker admitted that once he had chosen chess, he could not un-choose it. He could see too much in it:

It is too beautiful to spend your life upon. Many times have I managed to break with chess, yet I have always fallen in love with it again. I was too captivated by the conflict between ideas and opinions, attack and defence, life and death.

Labels: chess