Another walk

By 1930, Chiang Kai-shek had things pretty well sewn-up. The former warlord had succeeded Sun Yat-Sen as head of the Kuomintang, and following the Northern Expedition had largely reunified China under Nationalist rule. He'd then put down three defecting generals in the Central Plains War.

It hadn't come cheap. The Nationalist government was almost bankrupt, and there had been hundreds of thousands of casualties. And it hadn't been clean - the Central Plains War had been, even by the murderous standards of the place and time, an ugly affair.

Chiang had won the battles, but he had not yet consolidated political control. That made mopping up the Communists the new top priority. Following the most modern military doctrines, and with the help of good military advisors, he undertook a series of Encirclement Campaigns intended to annihilate the Communist enclaves.

Although the Nationalist forces were more numerous and better-equipped than the Communists, execution was uneven. The early campaigns in Jianxi, a key stronghold ("The Soviet Republic of China"), went badly. The Communists maneuvered effectively and even counter-attacked, focusing on understrength or inexperienced Nationalist units. They probably owed much of their success to the political, organizational, and military skills of this guy:

Mao Tse Tung, Prime Minister of the Soviet Republic of China, 1931

Mao had lived his entire adult life in a country adrift (he was 18 when the Qing were overthrown). The political battles were for keeps, and no one could be trusted. Jonathon Spence observes:

Certainly no historian working on twentieth-century China can deny that there were "moles" at work in many sections of the Nationalist Chinese army and intelligence agencies, moles placed either by the Nationalist Party, the Communists, or pro-Japanese sympathizers, and at times they influenced events in a decisive way. There were also double agents, on all three sides. All three sides had their own assassination squads.No one at the leadership level could afford to care about the body count. Certainly not the warlords, who killed Zhu De's wife and kids. Not Chiang, who had personally overseen the liquidation of thousands of Communists in Shanghai. Not the Japanese, who were warming up for the Rape of Nanking, before using the country as a chemistry experiment. And certainly not the Russians, who were just getting into the good part of the national fitness program we now call Stalinism.

It was not the kind of environment that would produce a Gandhi.

We don't know how great a strategist Mao really was, any more than we know who wrote his poems, did his calligraphy, or drew up his posters. In military affairs he certainly had significant help from Zhu De. But whomever was in charge was giving the Nationalists a very hard time.

Even so, the Nationalists gradually got the upper hand. On the fifth try (1933-34) they finally inflicted a decisive military defeat on the Communist force in Jianxi, and the whole enclave, under mixed leadership, tried to break out. The result was a military catastrophe. An anonymous Wikipedia author deserves credit for this fine account:

Initially, the First Red Army, with its baggage of top communist officials, records, currency reserves and other trapping of the exiled Chinese Soviet Republic, fought through several lightly defended Kuomintang checkpoints, crossing the Xinfeng river and through the province of Guangdong, south of Hunan and into Guangxi. At the Xiang River, Chiang Kai-shek had reinforced the KMT defenses. In two days of bloody fighting, 30 November to 1 December 1934, the Red Army lost more than 40,000 troops and all of the civilian porters, and there were strongly-defended Nationalist defensive lines ahead. Personnel and material losses after the battle of the Xiang river affected the morale of the troops and desertions began.What was left of the army paused for a leadership conference. "Go north, to fight the Japanese," Mao argued. If it could be done, something might yet be salvaged. If they got through, they could:

- Move the Red Army closer to Russia's political and material support.

- Confront the Japanese: It was still two years before the Rape of Nanking, but the Japanese were clearly the worst of the imperialist aggressors.

- Defang Chiang Kai-shek: If Chiang fought the Communists as they tried to fight the Japanese, he would appear to be placing his political ambitions above the welfare of the country.

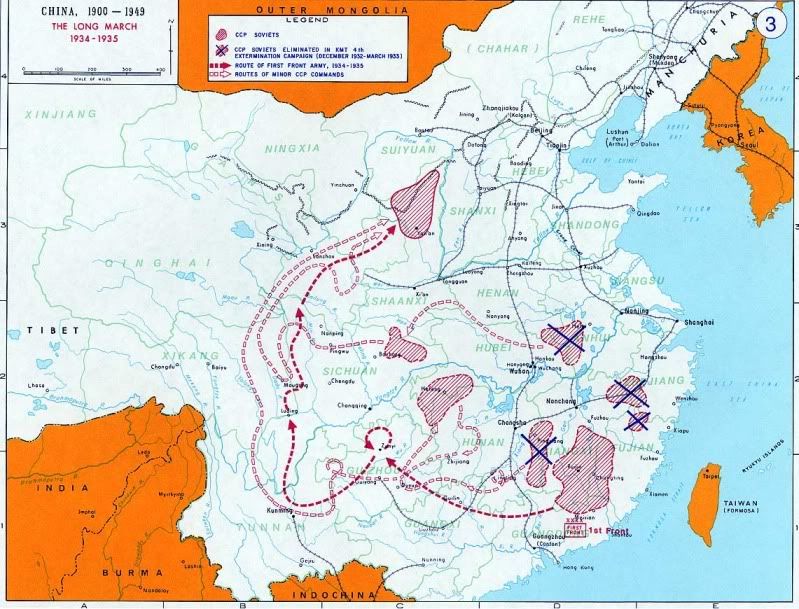

Route of the Long March (source: Wikipedia)

Morton again:

Those on the march covered 6,000 miles in just over a year, crossed twenty-four rivers and eighteen mountain ranges, five of them under permanent snow. They passed through twelve provinces and occupied sixty-two cities. By the end their numbers had been reduced to about 30,000 (some say fewer)... There were fifteen pitched battles and a skirmish of some sort almost daily.In 2003 two researchers retraced the route (their book is here). Their view that the route was shorter-than-advertised prompted a stern reaction from the Chinese government ("the 25,000 li of the Red Army's Long March are a historic fact and not open to doubt"). But lost in that controversy was this simple truth: it took the authors 384 days to cover the route...about the same time it took Mao's Army. And Mao's troops did it with bad equipment, food shortages, and people shooting at them.

You might imagine that they survived by ravaging the countryside and shaking down the peasants. But that's probably not what happened.

The Three Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention (tr. People's Daily):Both Morton and historian Stephen Uhalley argue that the Red Army actually followed these rules, and in so doing was able to draw a sharp contrast with the Nationalists, who behaved more "traditionally". In this brutal era, Mao was able to frame a story of a movement that acted with honor and decency toward common people. The people believed it.The Three Main Rules of Discipline:

- Obey orders in all your actions.

- Do not take a single needle or piece of thread from the masses.

- Turn in everything captured.

The Eight Points for Attention:

- Speak politely.

- Pay fairly for what you buy.

- Return everything you borrow.

- Pay for anything you damage.

- Do not hit or swear at people.

- Do not damage crops.

- Do not take liberties with women.

- Do not ill-treat captives.

(For a long time I wouldn't have believed a word of this, but now I do. A few years ago we had a guest in our house, a woman who had been born and raised among the Party elites in China. Another woman who was working for us broke a cup, and threw it out. Our Party-affiliated acquaintance was aghast, and earnestly tried to convinced the perpetrator to come to me, admit that she had broken the cup, take full responsibility, and throw herself on the mercy of the court. The cup-breaker, who was from Taiwan, saw little need for such gestures. It made for an interesting afternoon.)

But when you think of the corruption that was endemic in China in the first half of the 20th century, and the frustration of common people - imagine the political impact of that kind of commitment to honesty. Imagine being a peasant, and having troops show up - and not harm your family or steal your livestock. It reinforced the same crude but simple message Mao had been broadcasting to the poor every chance he got: we're on your side, the other guys aren't. Everyone is a bastard, and I am too, but I fight the foreigners and their puppets for you.

The Long March also left Mao more or less in charge of the whole enterprise. He said, in 1935:

The Long March is a manifesto. It has proclaimed to the world that the Red Army is an army of heroes, while the imperialists and their running dogs, Chiang Kai-shek and his like, are impotent. It has proclaimed their utter failure to encircle, pursue, obstruct and intercept us. The Long March is also a propaganda force. It has announced to some 200 million people in eleven provinces that the road of the Red Army is their only road to liberation.

Happy Days Are Here Again...

It was not a victory, exactly. It was a perilous escape under fire, like Dunkirk, the retreat from Chosin, or the Dalai Lama's flight to India in 1959. And it was a journey out of the heart of the country, to access foreign knowledge and resources, with the hope of returning and making a better China. In that sense, Mao's motivations were surprisingly similar to those of Xuanzang or Sun Yat Sen.

Another decade of fighting lay ahead, against both the Nationalists and the Japanese. We don't know much about that war. It was brutal (e.g., the Three Alls Policy) and personal (Nanjing was mostly - don't click on a full stomach - face-to-face murder). And it was massive - by the time the Japanese surrendered, there had been maybe 4 million Chinese military casualties, perhaps 2 million Japanese, and 15-20 million civilians.

We cannot know all the details, but we know the outcome. By the late 1940s a probable majority of Chinese were on board with the Communist world view. China had been the playground of foreigners and profiteers for too long. It was time to run them out and reclaim the country. It was the one argument that Chiang, with his personal wealth and U.S. sponsorship, could not refute.

Anyone who didn't get that world view - anyone who wouldn't get with the program, or who by accident of birth or place in society happened to be in the way - had to go. Mao would be cleaning house for a long time.

2 Comments:

So when are you going to write a book? Your writing really flows beautifully.

It's a long march to a fine essay.

Post a Comment

<< Home