Modernism for the Masses

I had thought of the comment of Mr. Lord on the subject “the use of mass production as a cultural technique” and it is a very significant question. The architectural vision Modernist is only one innovation unless it carries out widespread acceptance. And the elitism was certainly one of the failings of the Modernism.

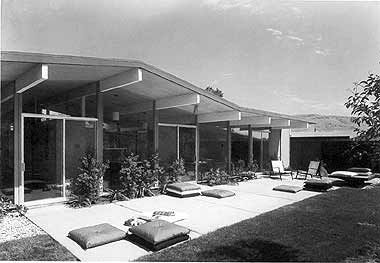

I wish to go to California because there was a man who, alone almost, brought Modernist architecture to the masses. Joseph Eichler made hundreds of Modernist houses in Palo Alto, San Mateo, and elsewhere in California. He was the first manufacturer to be useful itself of the skilful architects modernist, like A. Quincy Jones and Raphael Soriano, however he managed to maintain the costs of its product competing with the banal suburban houses of the ranch style of other manufacturers:

To indicate these houses were inspired by dogmatists like van der Rohe or Wright would not be correct. The construction of post-and-beam and open floorplans plans were certainly in the tradition Modernist, but there was no free use of van der Rohe's materials of luxury, not the sacrifice of Wright of livability in the name of the art. They were houses which maintained the structure and the vision of the Modernism, but interlocking allowed engagement of the human spirit, too.

I think that the greatest place of Eichler of all must be be The Highlands of the San Mateo, where Eichler built each house almost. Accessible houses established according to principles modernist for the normal people - I imagine it to be a beautiful dreamland, elegant structures in a rough air landscape, touched by wisps of cloud. It is my great dream with going there and to test this place.

Like you, Mr. Lord, Eichler was a political person. He was a Democrat and gave to the party much of money. He was also deeply moral about selling houses with the minorities. In the pleasant Design for Living: Eichler Homes, the son of Eichler remembers one controversial moment:

Eichler homes was the first large tract builder to sell houses to African-Americans… My father became involved on rare occasions when groups of homeowners demanded he refrain from completing a sale to African-American family… ‘I am not a fool,’ he told one such gathering. ‘If, as you claim, this will destroy property values, I could lose millions. You put up a lousy $500 and get a loan guaranteed by the government. You should be ashamed of yourselves for wasting your time and mine with such pettiness.’This, I think is the society wedding of the spirit American, optimistic, egalitarian, and of the correct vision Modernist of the great design for the masses.

Mr. Eichler died in 1974, but he was a great man, a great spirit. I hope for a certain day to come to see this paradise Modernist in the clouds.

2 Comments:

Monsieur-

Your interesting essay must necessarily constrain me again to address this question of modernism, which like so many social or creative movements, is a shorthand for a set of complex developments in the arts generally that tends to obscure foundational differences in mindset, goals, and accomplishments.

First, no discussion of modernism can occur without its political context: in particular, the difference between pre-war European and post-war American modernism.

So much of the modern style that still influences basic design from IKEA to Target (with all the breadth of modern experience that implies) has its orgins in the progressive rejection of aristocratic, perhaps "Edwardian" design history at the opening of the 20th century, which had an interesting stopover, and a strangely proto-fascist one at that, at the otherwise laudable Arts and Crafts movement, itself a reactionary movement against one of the drivers of design at that era: the industrial revolution.

Obviously, the LOOK of what we now tend to think of as modernism has direct origins in the Russia constructivists and the subsequent german-dominated Bauhaus movement: an influence, utterly devoid of its political, anti-imperialist origins, that you can plainly see walking into Crate and Barrel, which hardly qaulfies as a font of neo-Leninism. At the same time, in related movements like the Italian futurists, drives towards utopian, anti-aristocratic movements had vicious cousins in the adoration of the mechanical as metaphors for society - the machine was the ideal (I think of a small, 1940 sculpture at the University of Washington titled "Mankind liberated by Machinery" as a quaint if stimulating oddity) and one direct result was the rapid adoption of early modern industrial design by every violently evil political movement in the world simultaneously. The fact that the Italian fascists, and the German fascists, and the Stalinists all gobbled up the supposedly progressive and democratic design movements of the moderns in architecture with barely a ripple of protest in Hitler's moustached suggests that what was important in the industrial and architectural design to larger political movements was cheapness, mechanization, and to a lesser extent, prestige from copping supposedly avant-garde design movements. Even after the war, Bauhaus cleanliness, econonmy and restrain was immediately swallowed whole by the bourgeois capitalists in America. In other words, European modernism, as an philosophy intended to influence society, and especially as a political movement, despite most of its intents, was a dismal failure.

The problem goes back within the design itself to the metaphor of the machine, the hatred of flourish, suspicion of beauty, and an easily corruptable desire to design a utopian society.

At the same time, on the fine art side, the modernist desire had progressed from the aggressively transformative in cubism to an attempt to liberate the unconscious in surrealism, and the sensual in Picasso and Matisse, and by extent, even political, liberate everyone by self and social experimentation, a huge element in fine art that influences contemporary work hugely.

An extremely understandable suspicion of utopian politics post-World War II led to greater concentration and investigation of the self and the personally intellect after the war among the Americans in particular; witness the fall of Diego Rivera and the rise of the New York school. Yet the ab-ex painters were definitely political, progressive, essentially socialist or Rooseveltian at their most conservative. But it was jazz, and empahtically not architecture, that shared and drove the modernist ethic in fine art, perhaps throughout the century. Painting had an very direct and conscious relationship to post-war Jazz. Coltrane and DeKooning were aesthetically far more alike than DeKooning and any post-war architect, for example. The architects, driven I think by the inevitably utopian ego peculiar to their work, were still largely playing around the shallow end of the pre-war Euro-modernist pool.

You mention, monsieur, a modernist who had democratic ideals and a fine effect in some ways, other than of course city design, for which his methods were something of a total catastrophy, utterly dependent on the car. But he did share the critical interest of the moderns in jazz and visual art in political liberation through personal liberation, and vice versa.

We are left with Mondrian, the "harmless religious crank," blithely sitting on the brushed aluminum rail of Bauhaus design, straddling modernism in fine art and modernism in architecture, alone with his dry dutch version of "Jazz," color-coded in little squares on masking tape.

Yes, exactly.

I thought after Eichler the trail must go stale. But there is another. I will write you about him soon.

Post a Comment

<< Home