Dropping in at Salisbury

During our UK trip I had to concede one day to the generic Tourist Tour - Stonhenge (mobbed), Bath (mobbed), and along the way...Salisbury Cathedral.

I thought of Salisbury as a bit of a throw-in on the tour - a place near the lunch stop where they could move us to a little less-congested spot for a while. Salisbury is unique for several reasons. Its churchyard was cleared in the Victorian era, creating open space around the structure that gives you room to step back and look at it, and to walk around in. It towers majestically over that open space: its 6,500 ton spire is the highest in the UK, and would likely have toppled by now had not Christopher Wren put in tie beams in 1668.

Salisbury also stands out for its architectural coherence. Built in the relatively brief span of 38 years (1220-1258), it is a pure exemplar of the Early English Gothic style.

And then there's the black man standing up there. Wait, what?

Yes, there, at the left hand of St. Thomas of Canterbury, the fellow holding the coffee mug. Excuted by Sean Henry, the statue is one of over 20 that will be in residence at various places around the cathedral through the end of October. (The BBC offers a fine photo tour here.)

Now ordinarily I have no patience for this sort of thing, because it never works. The modern has very little to say to the ancient, I believe. Because life is so convenient now - because our genuine suffering is so infrequent - I find it hard to imagine that any modern artist can add much to what is already there. Adult life expectancy when this place was built was around 35 years, child mortality was probably 30-50%, there were no treatments for infectious diseases, appendicitis, etc. We know much more than they did about many things, but suffering? The meaning of life? I doubt it.

But I found Henry's sculpture arresting, as well as several others in the installation. Henry makes a valid point - the saints are already well-represented, but what about the people who lived here and came here? "I'm interested in memorialising the everyday," he says.

Henry adds, but does not intrude. The statues he has placed look like they belong there - they express some of the sentiments that perhaps motivate someone to go to church in the first place, such as this fellow who has taken refuge from the institutional madness of his career:

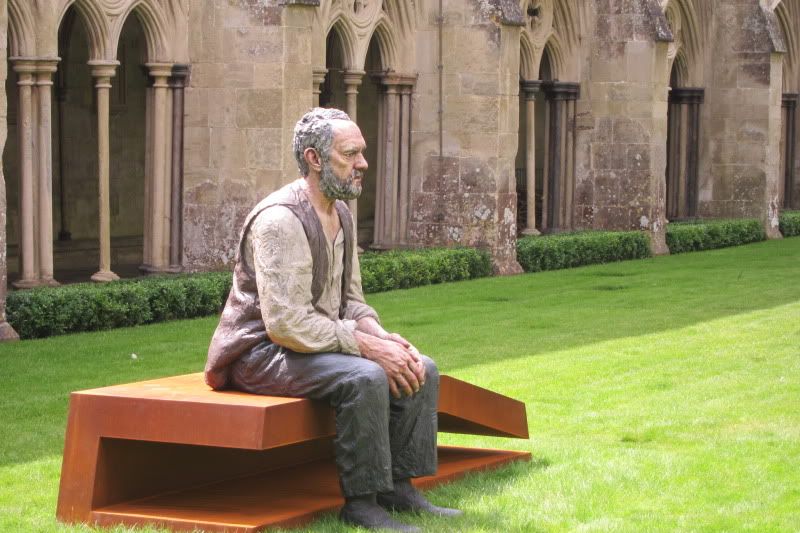

Or this man (I thought he was real for a moment) who could have walked out of a field at almost any time in the past thousand years:

The experience of the exhibition is not shocking so much as evocative. We are so used to walking through empty cathedrals, Henry reminds us of a time when they were full, and necessary, and shows us what kind of people went there.

The cathedral itself is magnificent, and while I still have my reservations, Henry's installation is beautiful and well-judged. It reminds us gently of things we might prefer not be reminded of, without disrupting the original intentions or current purpose of the structure. It deserves respect at least, maybe quite a bit more.

3 Comments:

That is indeed a great re-siting for realistic sculptures. To be fair, it is really is another latter day Renaissance F.U. to the builders of the Cathedral, whose aesthetics were specifically hostile to the everyday.

I must dispute your contention that modern artists have little to say to the past, or that genuine suffering is so rare now. Aside from any of the last 100 years providing plenty of opportunities for suffering on a genocidal scale, people's basic ranges of emotion have not changed, and the assaults on human dignity are daily.

There is much more aggregate economic happiness; that does not translate into a lack of suffering. Even in the West, while we may live longer, we do not want for death, alienation, physical and emotional pain, societal and personal assaults on dignity and identity. We do not want for loneliness and we do not for wanting, all of which are the ancient subjects for art; although in the modern world that personal rather than religious suffering has flowered as a subject for art.

We haven't lost suffering. But we have lost much of the ability the focus on the exact nuances of physical space to which ambitious architects of the past were so well attuned. In the world of screens, the real gets short attention, and blank walls collide endelessly into blank walls.

I guess another way at my point is that we live much of our lives under anesthesia, or at least sedation. With short attention spans and abundant entertainment available on demand, people can tune out almost any unpleasant experience nowadays. In the old days that option wasn't really available to you, so you had to face it and deal with it.

I don't mean that as a knock on modern art, which is often about the shock of facing something you are trying to look away from.

Appreciate the extension. It's a point: the sedative of mass culture, the blizzard of images and social messages, is both the salve to and the cause of alienation, the hollowness in our sense of place and identities. We have gained enormous freedoms over the content of these messages, and lost much of their relevance and power. Wonderfully, our voices have a toehold in mass culture now, but the damage to personal and community relationships, as screens supplant faces, is very real and growing worse.

Post a Comment

<< Home