An Occurrence at Varda Bridge

When James Bond takes his bullet in Skyfall, he is grappling atop a train speeding across the Varda Bridge (which, as every schoolchild knows, was built by the Germans in 1912 as part of the Berlin-Basra railway).

And then, plunging 300 feet into the river below, he dies:

Encompassed in a luminous cloud, of which he was now merely the fiery heart, without material substance, he swung through unthinkable arcs of oscillation, like a vast pendulum. Then all at once, with terrible suddenness, the light about him shot upward with the noise of a loud splash; a frightful roaring was in his ears, and all was cold and dark...

That is when Adele begins to sing that beautiful, mournful song:

This is the end,

Hold your breath and count to ten...

And then, through the magic of movie fantasy, Bond is resurrected to galavant and gavotte through Shanghai, London, and various other exotic locales, and also Scotland. Entertainment ensues, and the stage is set for another 50 years for the franchise.

Or is it? I hugely enjoyed Skyfall for its inspired action sequences, homage to the best aspects of the Bond genre, and playful sense of humor (e.g., Chekhov's knife). But as I contemplate it, I believe it may also be read as an artistic achievement along the lines of An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge - an obituary, accompanied by the intoxicating hallucinations of a dying man:

For Some People That's Thursday

After all, this is what the Bond movies have always been - lavishly illustrated adolescent fantasies, propelled commercially by the elongation of adolescence in the general population over the past 50 years.

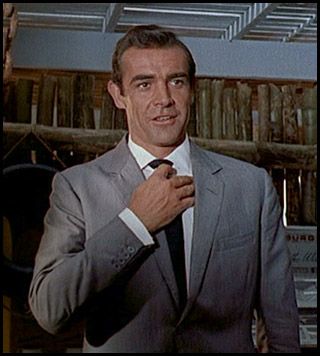

The Bond story has a clear beginning - in literature it begins in the study of Ian Fleming during the Cold War; he named Bond after the author of his ready-to-hand birdwatcher's guide because he liked the mildness of the name. The celluloid Bond came to life when director Terence Young took Fleming's work, and his own cultural sophistication, and mapped them onto a Scottish footballer:

Cleans Up Well

Fleming had originally imagined Bond's face as more in the Hoagy Carmichael category. He did not want Connery, saying "I'm looking for Commander Bond and not an overgrown stunt-man," but after seeing Dr. No (and, presumably, the residual checks), he was converted. Stories after 1962 were written with Connery's countenance in mind.

The other primary tension between the Fleming Bond and the movie Bond was never really resolved, however. In Fleming's stories, Bond is flesh and blood, and decidedly mortal. In the movies he is generally super-powered and immortal, and this is accompanied by a carefully preserved spirit of farce. One achievement of the franchise, if you can call it that, is to entertain audiences without threatening them. In most of the films, even the better ones, there is no moment in which we fully suspend disbelief, no encounter with anything resembling an actual person.

Skyfall is generally faithful to these conventions, and of course there is no attempt to contravene the prime directive:

This is just a hook-up, you're cool with that, right?

Bond's taste in women remains impeccable. In Skyfall even his warmup girlfriend is hotter than anyone I have ever met in real life, except of course for my wife and the Corresponding Secretary General.

But Skyfall does, as Adele promises, offer an ending to what Fleming began. To do so, it restores the literary Bond, the one that bleeds, and can die. It asks out loud if he should perhaps have stayed dead. And as the action becomes more extreme, imagistic, and absurd, we begin to wonder whose dream this is.

Perhaps it is Bond's, in his last moments beneath the Varda Bridge, when his life, and the life that might have been, flash before him. Taken as live action, Skyfall allows Bond the opportunity to tie up myriad loose ends, to hold M in his arms and call her Mother, to make everything right and report for duty good as new. But deep in our hearts we know that isn't on offer. Life rarely affords us such opportunities, least of all to middle-aged soldiers who have lost a step, no matter how much they might desire them. And so our adolescence ends.

He stands at the gate of his own home. All is as he left it, and all bright and beautiful in the morning sunshine. He must have traveled the entire night. As he pushes open the gate and passes up the wide white walk, he sees a flutter of female garments; his wife, looking fresh and cool and sweet, steps down from the veranda to meet him. At the bottom of the steps she stands waiting, with a smile of ineffable joy, an attitude of matchless grace and dignity. Ah, how beautiful she is! He springs forwards with extended arms. As he is about to clasp her he feels a stunning blow upon the back of the neck; a blinding white light blazes all about him with a sound like the shock of a cannon--then all is darkness and silence!

Peyton Farquhar was dead; his body, with a broken neck, swung gently from side to side beneath the timbers of the Owl Creek bridge.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home