Soldiers of the Great Struggle

I am sorry to have let another Victory Day pass by without timely comment, so this will have to serve as my Memorial Day post. As always the proceedings in Russia were, to my eyes, both alien and beautiful. In contrast to American military events, the Russian ones seem more serious, more resolute, and more aware of the contingency of war. American military events seem to always have an optimistic character. Sure we've had our defeats - but we leave them behind on parade day. The Russians, on the other hand, always march with their eyes on history...

1941

The Victory Day parade seems to remember defeat as well as triumph, and to memorialize not only the fallen, but perhaps even the marchers themselves. It is a show of strength, but to my eyes also a reminder that (as Stalin said) "there are no invincible armies" (video of German POWs marching through Moscow in 1944 here).

The marchers know they are expendable, and that is the precise nature of their value. If the Russian military parade stands for anything, it stands for the resolve of an entire people, of the power of sacrifice in the face of predatory and merciless enemies.

2009

I have always wished an American president could go there, and in a public forum, say something about all this. Something to make them realize that someone over here has an inkling of what they have been through, what they are willing to endure:

You know already that America is a fortunate country in many ways. And you should know that we understand...we have not been tested as you have been tested. We realize - but can never truly comprehend - the sacrifices that were made in the Great Patriotic War. We fought our battles, too, but they were not fought on our soil, amongst our homes, against an enemy determined to enslave us.Or words to that effect...

For all Americans let me express here our profound respect for the sacrifices made along the Volokolamsk Highway...at the Grain Silo...at Prokhorovka. Whatever our differences, do not imagine that we are unaware of the extraordinary determination and bravery of your people. And join us in our efforts to make the world a place where such sacrifices need never be made again.

It will never happen of course. But I wish Americans could understand better the magnitude of it all. Soviet military deaths were in the neighborhood of 10 mm during the Great Patriotic War. This included 3.6 mm POWs (most captured in the opening German offensives) who died in German captivity. That's roughly the population of Chicago. Put another way - that's about how many soldiers died on all sides in World War I. The civilian casualties are impossible to estimate, but maybe another Chicago, or two.

It wasn't just the young men, either, as it had been in World War I. The chess master Alexander Ilyin-Genevsky was about my age when he was killed in an air raid during the Siege of Leningrad.

Well, they say it was an air raid. Ilyin-Genevsky was an original Bolshevik, one of the few to survive Stalin's purges of the 30s. Most shared the fate of Bukharin, condemned to die at show trials in the name of a revolution that had been regularized, commoditized, and turned against them. Yet Bukharin found meaning in it all:

For three months I refused to say anything Then I began to testify. Why? Because while in prison I made a revaluation of my entire past. For when you ask yourself: "lf you must die, what are you dying for?"-an absolutely black vacuity suddenly rises before you with startling vividness. There was nothing to die for, if one wanted to die unrepented. And, on the contrary, everything positive that glistens in the Soviet Union acquires new dimensions in a man's mind. This in the end disarmed me completely and led me to bend my knees before the Party and the country. And when you ask yourself: "Very well, suppose you do not die; suppose by some miracle you remain alive, again what for? Isolated from everybody, an enemy of the people, in an inhuman position, completely isolated from everything that constitutes the essence of life..." And at once the same reply arises. And at such moments, Citizens judges, everything personal . . . all the rancour, pride, and a number of other things, fall away, disappear.The old Bolshevism was to be excised, and he understood that as its last great avatar, he too must go. But not quietly. In his final testimony he consistently admitted responsibility, admitted guilt, admitted the fact of his criminality - while denying each specific charge laid against him. He was guilty because the State said so - this made it a simple fact - but not because he had actually done anything he was accused of. Without resources or assistance of any kind, he challenged the state prosecutors, outmaneuvered and embarrassed his tormentors, and ultimately challenged those who would survive him to dedicate their lives to the betterment of the nation. To draw these distinctions in the crucible of a hostile courtroom was a fitting culmination to his career.

So maybe Ilyin-Genevsky (so named because he had been a political exile in Geneva for a time) wasn't killed by the Germans. It was dangerous to be an old Bolshevik. We'll never know for sure - there were a lot of viruses going around in 1941.

Ilyin-Genevsky had a trial of a different sort, and from it we have a different kind of testimony. I present as evidence the game of chess he played, at the Moscow International Tournament of 1925, against Jose Raoul Capablanca, Chess Champion of the World. To face Capablanca at that moment - at the height of his powers and always surrounded by curious and admiring spectators, was the supreme test of a chess master:

Capablanca (r) faces Bogoljubov later in the tournament.

As they sat down to play in the Hotel Metropol, Ilyin-Genevsky must have known he was facing the best chess player in the world, a man who had said "I can draw at will against any master." The Russian was outclassed, but he was not a patsy - Chessmetrics estimates that he was one of the 20 or 30 best players in the world at that time.

He must have felt a sense of responsibility. After all, he had promoted chess as a revolutionary idea - a way to encourage analytical rigor in military training and scientific thinking among the populace at large. He had personally organized the first Soviet Championship in 1920. As one of the founding fathers of Soviet Chess, he had a duty to play well. Still, he knew he was a backwater guy, a club champion - playing a man whose game was so logical, clean, and irrefutable that it is questionable whether he even had a 'style'. Capablanca's style was to always play the right move.

The game evolved as a simple closed Sicilian. Capablanca, playing White, advanced on the kingside, centralized his knights behind the pawn wall, and applied pressure in the center. Ilyin-Genevsky sought thematic counterplay on the queen's side. And then...he thought he saw something. No...he was sure he saw something.

At move 29 Ilyin-Genevsky's queen penetrated the White position, unsupported. At move 31 Capablanca moved a rook to attack the intruder.

Ilyin-Genevsky left the queen where it was, and pushed a pawn forward, positioned to recapture. He was offering a queen sacrifice to the best player in the world.

Capablanca accepted the sacrifice...and, seven moves later, resigned.

Soviet chess had arrived, and would be around for a very long time.

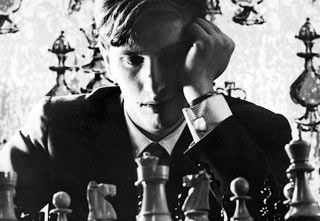

It wasn't until Capablanca's most fervent disciple dared to confront it that the Soviet chess machine began to lose its aura of invulnerability. Unfortunately for Bobby Fischer, it was essentially a suicide mission. Studying on his own, without state support, without the benefit of the easy draws the Soviets gave one another to stay fresh for him, he took the fight to them, and won outright.

When Fischer died, the Laird asked about an obituary. At the time I had no answer. I could only think of that line from Once Upon a Time in the West - Fischer, in my mind, had died a long time ago. He had won, but lost his sanity in the process.

So here is the obituary: Bobby Fischer was one of the few genuine tragic heroes of modern times. Like Bukharin and Ilyin-Genevsky, he risked everything to challenge his antithesis - the immense calculator, the Other, the Beast. It is not so easy to make such a challenge - first you must become brilliant, then you must decide to fight instead of living a nice quiet life, and agree with yourself that the risk of annihilation is an acceptable one. Such men are so rare they hardly ever meet one another (Fischer was fortunate to meet Bronstein early in his career). They fight, and usually are destroyed, in profound loneliness. Let Eliot have the last word:

And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

Labels: chess

3 Comments:

A compelling and fascinating essay.

"Genius is present in every age, but the men carrying it within them remain benumbed unless extraordinary events occur to heat up and melt the mass so that it flows forth." - Diderot.

Speaking of Memorial Day, I was able to visit the last Seattle built B17, the only f model remaining, under restoration at the soon to be demolished Plant #2 today, with the guide of a veteran pilot of 30 WWII missions (!). More on this later.

The problem with this little format we're working in is you have to leave a lot out.

One of the real tragedies of Communism 2.0 was that implementation required erasing a lot of the more admirable components of Communism 1.0 . In particular, people who were temperamentally inclined to act on problems they might have with the government needed to be removed from the picture. It was more urgent to remove those whose actions might actually accomplish something (Bukharin and Ilyin-Genevsky as prime examples).

The price, of course, was a loss of dynamism, and the original motivating spirit of the revolution. Grey Party men replaced the revolutionaries, and quietly and gradually started extracting the same rents and privileges that had accrued to the prior bourgeoisie.

This drove Mao nuts. I think he probably would have liked to have the Bombard the Headquarters poster back, but it's not hard to see where it came from.

Here is a modern example of the species mentioned in the original post. This guy's life hangs by a thread, but he plays on.

Ian Buruma elaborates here.

Post a Comment

<< Home