World War I was not a romantic war, or, at least, it was the war that wrecked the

romantic notions of the general public, a cluster of illusions that had survived even the Civil War. But in 1914, before the Marne, Flanders, the Somme, Verdun, it was still possible to imagine that there could a bit of romance to it all. Who knew? It had been almost a hundred years since the last big war in Europe.

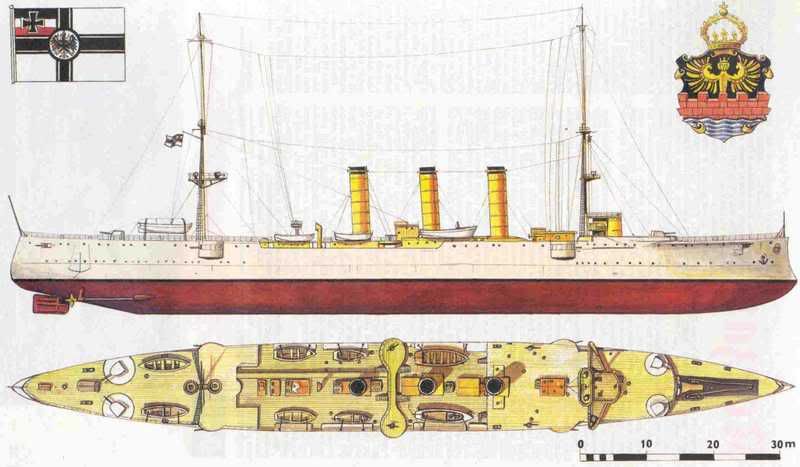

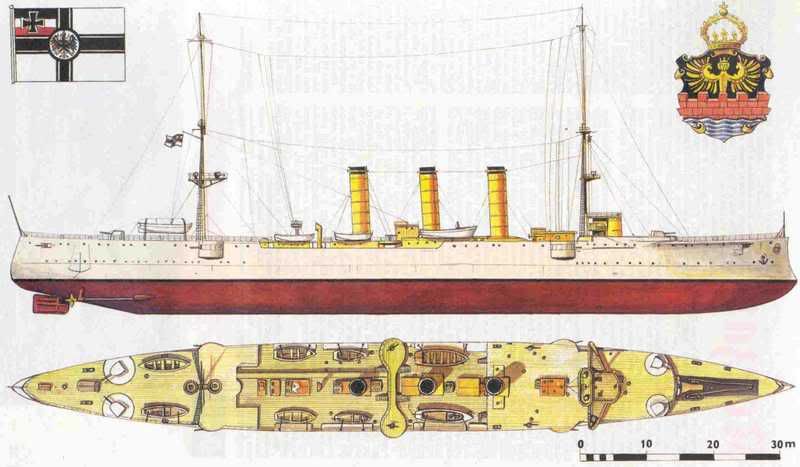

And in those early days of the war, one German ship, SMS

Emden,won notoriety and admiration worldwide for its solo raiding in the far east. Emden was a light cruiser - launched in 1906 she was not of the latest design, but very functional. She could make 23 knots getting to the fight, and had ten (slightly obsolete) 4-inch guns and two torpedo tubes to deploy when she got there.

Decked out in white, the ship exuded class and grace. She was an ideal ambassador abroad for an ambitious Germany, and was on station in China when the war broke out.

Now, let me ask you something. This has always kind of confused me. Why is it that the Germans, with all their emphasis on strength and manly confrontation on land, suddenly turn

all Frenchy into finesse players when they get out on the water? They love their commerce raiders. Even when they get a decent battleship or two, they put them in a commerce raider role. Why, in WWII, did the Germans not take

Bismarck,

Tirpitz,

Scharnhorst,

Gneisenau and just get after the British fleet? We know from

the voyage of Bismarck how well that ship could fight, but why on earth would you deploy it with just one or two escorts? Why,

after almost winning outright at Jutland, would the Germans avoid all future fleet-to-fleet contact?

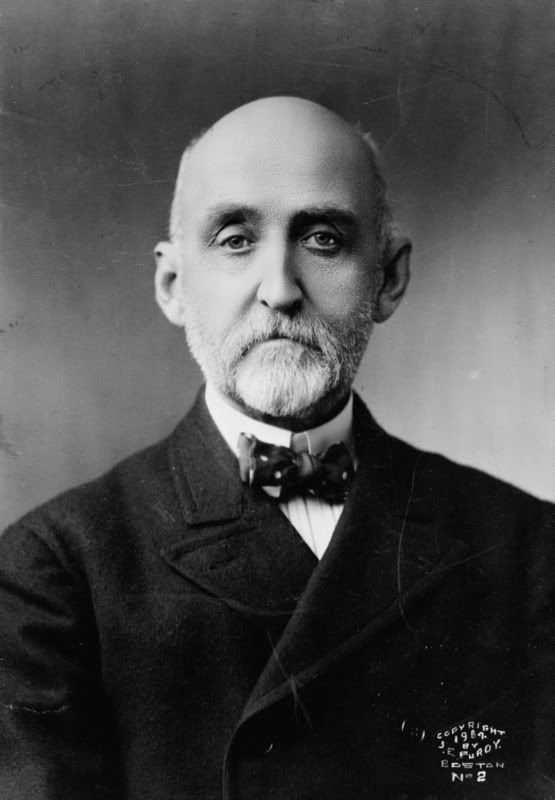

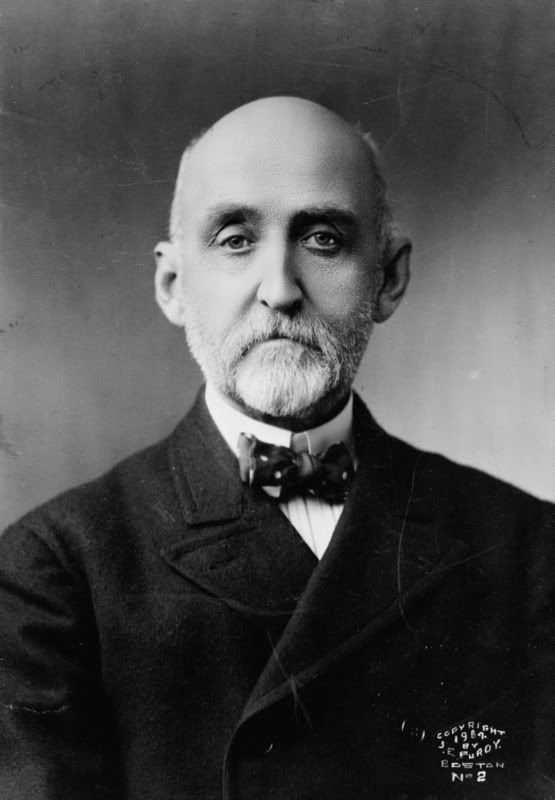

It really is strange. Through two world wars, the Germans ignored

A.T. Mahan's Prime Directive - take what you've got, and go for the other guy's throat.

Destroy the opposing main force and seize control of the oceans. Don't piss away your resources with commerce raiding!

"It is not the taking of individual ships or convoys, be they few or many, that strikes down the money power of a nation; it is the possession of that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy's flag from it, or allows it to appear only as a fugitive; and which, by controlling the great common, closes the highways by which commerce moves to and from the enemy's shores."

Why did the Germans not heed this advice? The answer, I would argue, is the voyage of

Emden. She made it look so easy.

The story is simple enough. The war starts and

Emden is in China. Her captain, Karl von Müller, is not going to get trapped in port the way

the Russians did at Port Arthur. He gets underway immediately, joins up with the German Pacific squadron long enough to get his orders, then goes on a

solo mission of random mayhem through the East Indies. Some highlights:

- 9/10 - Captured ship with a lot of soap - this was good because they were low on soap

- 9/18 - Shelled Rangoon

- 9/23 - Shelled Madras

- 9/25 - Emden featured in soap advertisement in Calcutta

- 9/26-9/29 - Six prizes off Sri Lanka (this is where Wikipedia could really use a factchecker... I have no idea if this is true but it's too good not to use: "Sri Lankan mothers frightened their children with the Emden bogeyman, and to this day a particularly obnoxious person is referred to as an Emden, in Tamil.")

- 10/1 - Pissed-off Churchill writes "I wish to point out to you most clearly that the irritation caused by an indefinite continuance of the Emden's captures will do great damage to Admiralty reputation."

- 10/15-10/20 - Seven prizes off Kerala

- etc. etc.

I should note here that this is all done somewhat humanely, especially with the merchant ships. Müller takes prisoners and treats them well. He offloads civilians in various ports and on neutral ships, and is actually cheered by them on several occasion.

At this point there are dozens of ships of various nationalities (British, Australian, Japanese, and Russian) chasing

Emden around. I would think Müller would be working on his exit strategy...and perhaps he was, because his next stop is Penang, due east, and on the way back to the Pacific.

On October 28th,

Emden sails into Penang harbor (with a fake fourth funnel to make her look like a British cruiser), hoists her German flag, and blasts the Russian cruiser

Zhemchug to smithereens. (This does nothing for the reputation of Russian naval arms as the Captain was supposedly at a brothel on shore.) A French destroyer pursues

Emden and is sunk for her trouble.

And just like that...like the Shadow...

Emden's gone again.

Around this time

Emden is awarded the Iron Cross, one of only two ships to ever receive this honor. This may not seem like a big thing to you, but the Germans take it pretty serious, seeing as how

the current Emden still wears the insignia (more on the modern ship

here).

It was all going pretty well, but even the hottest hand can cool off in a hurry. A few weeks later Emden is minding its own business, trying to destroy a major British wireless station, when it runs into

Sydney.

Sydney is bigger, faster, and better-armed than Emden, and blasts the crap out the pretty German ship.

Emden's shells mostly bounce off the inelegant, but extremely well-armed, Australian. The German ship is run aground to prevent sinking.

Ultimately, this message is sent:

HMAS Sydney, at sea

The Captain, HIGMS Emden

Sir,

I have the honour to request that in the name of humanity you now surrender your ship to me. In order to show how much I appreciate your gallantry, I will recapitulate the position.

(1.) You are ashore, three funnels and one mast down and most guns disabled.

(2.) You cannot leave this island, and my ship is intact.

In the event of your surrendering in which I venture to remind you is no disgrace but rather your misfortune I will endeavor to do all I can for your sick and wounded and take them to a hospital. I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

John Glossop

Captain

Vladimir Kroupnik offers this fine summation:

So ended a voyage of 30,000 miles, in which a single obsolescent cruiser had done damage worth at least 15 times the cost of building her--more than 5 million pounds sterling. She had sunk a cruiser, a destroyer and 16 merchant ships, coaled 11 times from three captured colliers and had bombarded oil facilities in the heart of the British empire, while disrupting transport, raising the price of rice and insurance in the Indian Ocean region and drawing the attention of 78 warships from four navies. Emden, however, had also managed to leave behind a record of daring, resourceful enterprise and chivalry that endeared her even to her enemies. A typical epitaph appeared in The Telegraph in London: "It is almost in our hearts to regret that the Emden has been captured and destroyed....There is not a survivor who does not speak well of this young German, the officers under him and the crew obedient to his orders. The war on the sea will lose some of its piquancy, its humour and its interest now that the Emden has gone."

Think of that - in 1914 one could speak of humour and piquancy in the sea war. It was still six months before Lusitania.

I don't know why I care so much about Emden, except that, perhaps, its passing marked a broader loss of innocence.

Here is a nice Youtube video about the ship.